I came off the trail in Flagstaff, at Mile 208.5 - almost a hundred miles earlier than last year.

What went wrong?

Nothing.

This is the difficult truth: I had no reason to drop out.

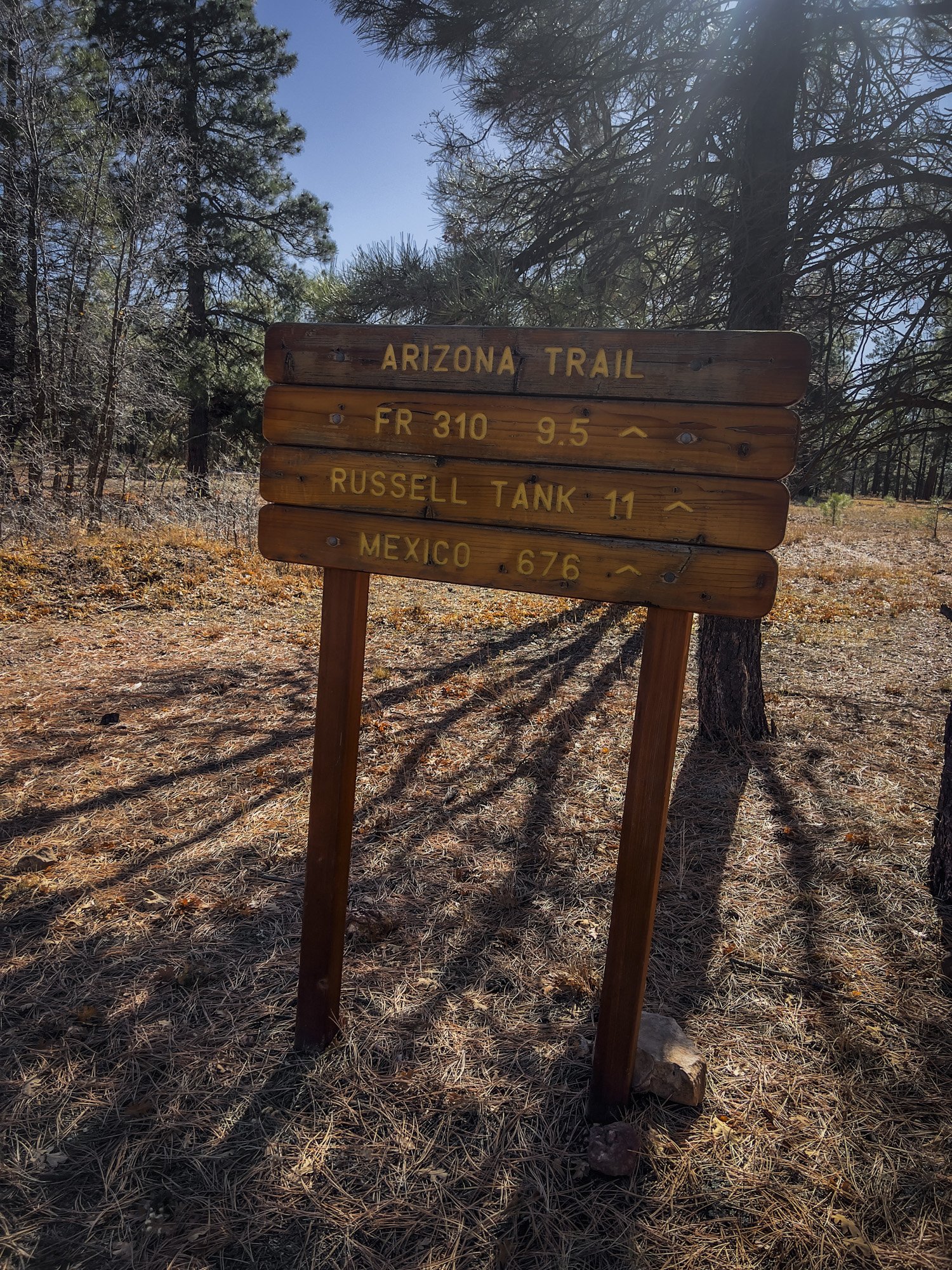

I made it across the Grand Canyon, and through the high country of the San Francisco Peaks with their early snow. Despite taking a nero (nearly zero) day to recover from the difficulty of climbing out of the Grand Canyon with heavy weight, I was a mere two miles behind record schedule - and on track to be comfortably ahead of record pace within just one more day of walking. Yes, a lot can happen over 590 miles and two additional weeks of trail time, but the nature of an Unsupported speed record suggests that you should get faster over the course of the attempt rather than slower. That’s because your initially insane food weight diminishes with every passing day, eventually leaving you with nothing more than a lightweight backpack. As long as you find a way to not break yourself, your energy levels, or your gear, during the first half of an unsupported long-distance hike, the miles towards the end become lighter and more manageable.

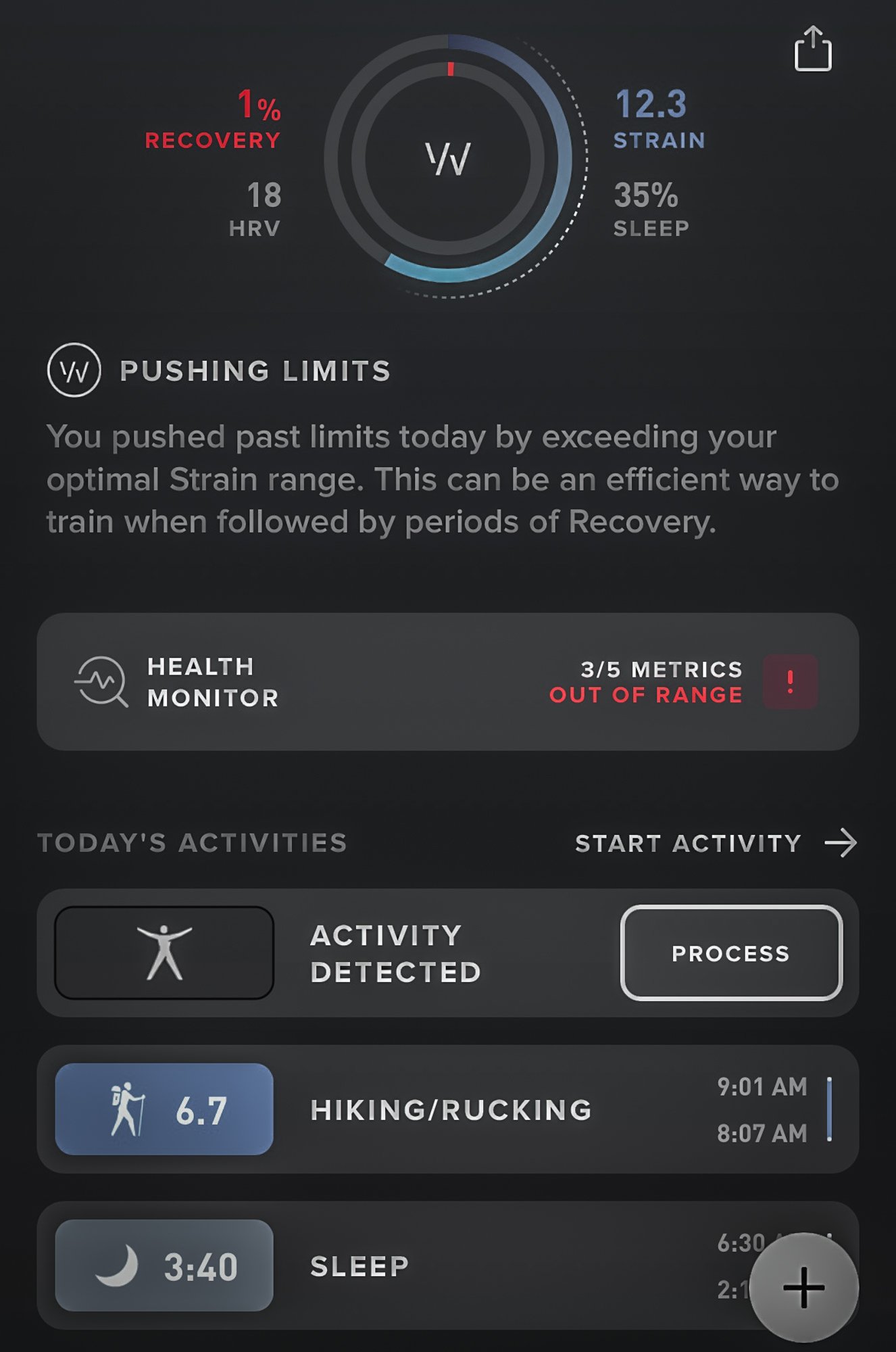

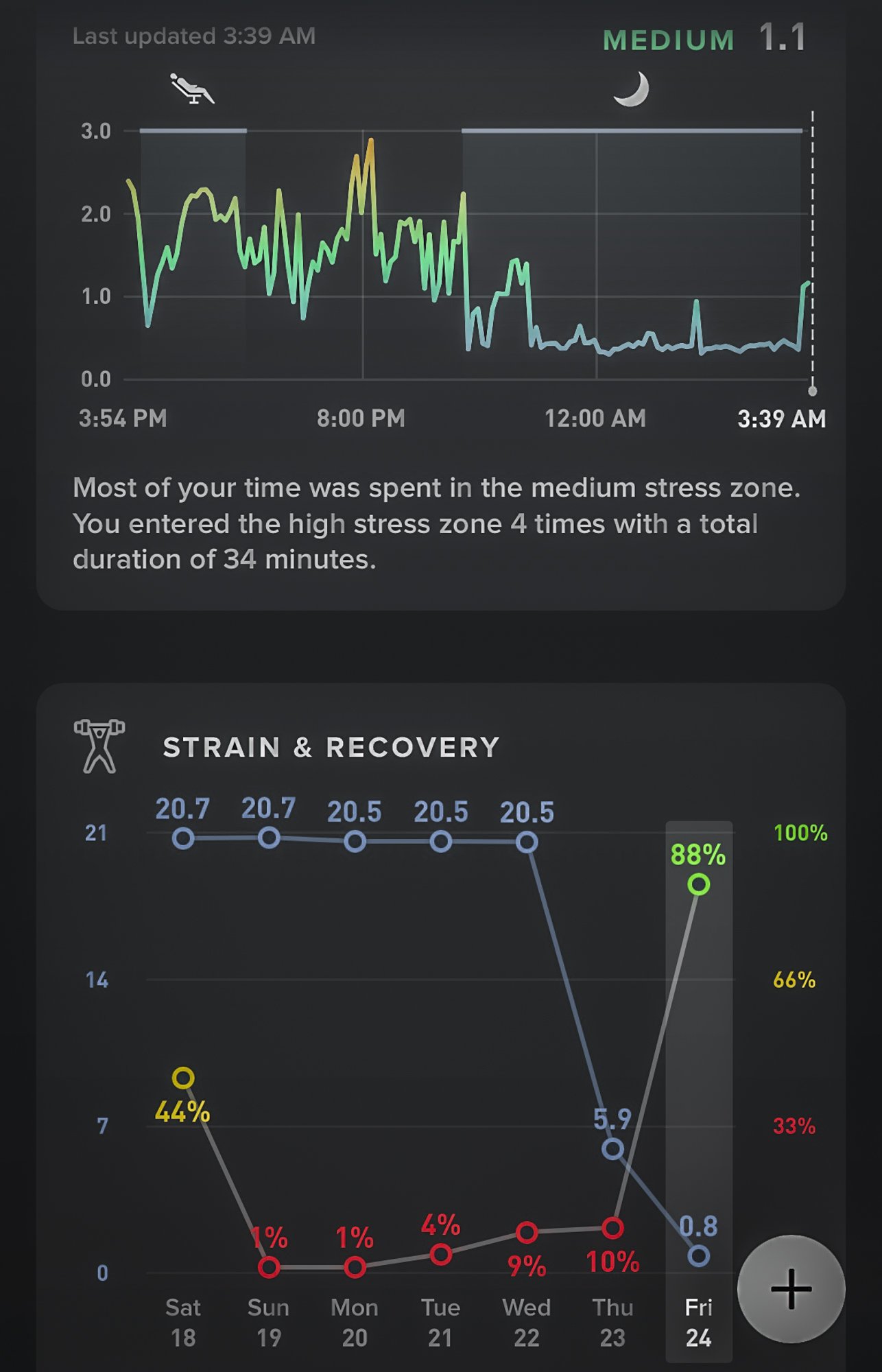

How did my energy management fare? I had been sleeping plentifully, and mostly well. My food plan was on point - I ate each day what I was supposed to, all 4,500 calories of it, never bonked, and never went to bed hungry. I haven’t yet had a chance to weigh myself but I think I didn’t lose a single pound in this 200 mile week; the ultimate testament to fueling appropriately.

So what went wrong?

Did my gear break? No - with a few minor issues everything worked beautifully.

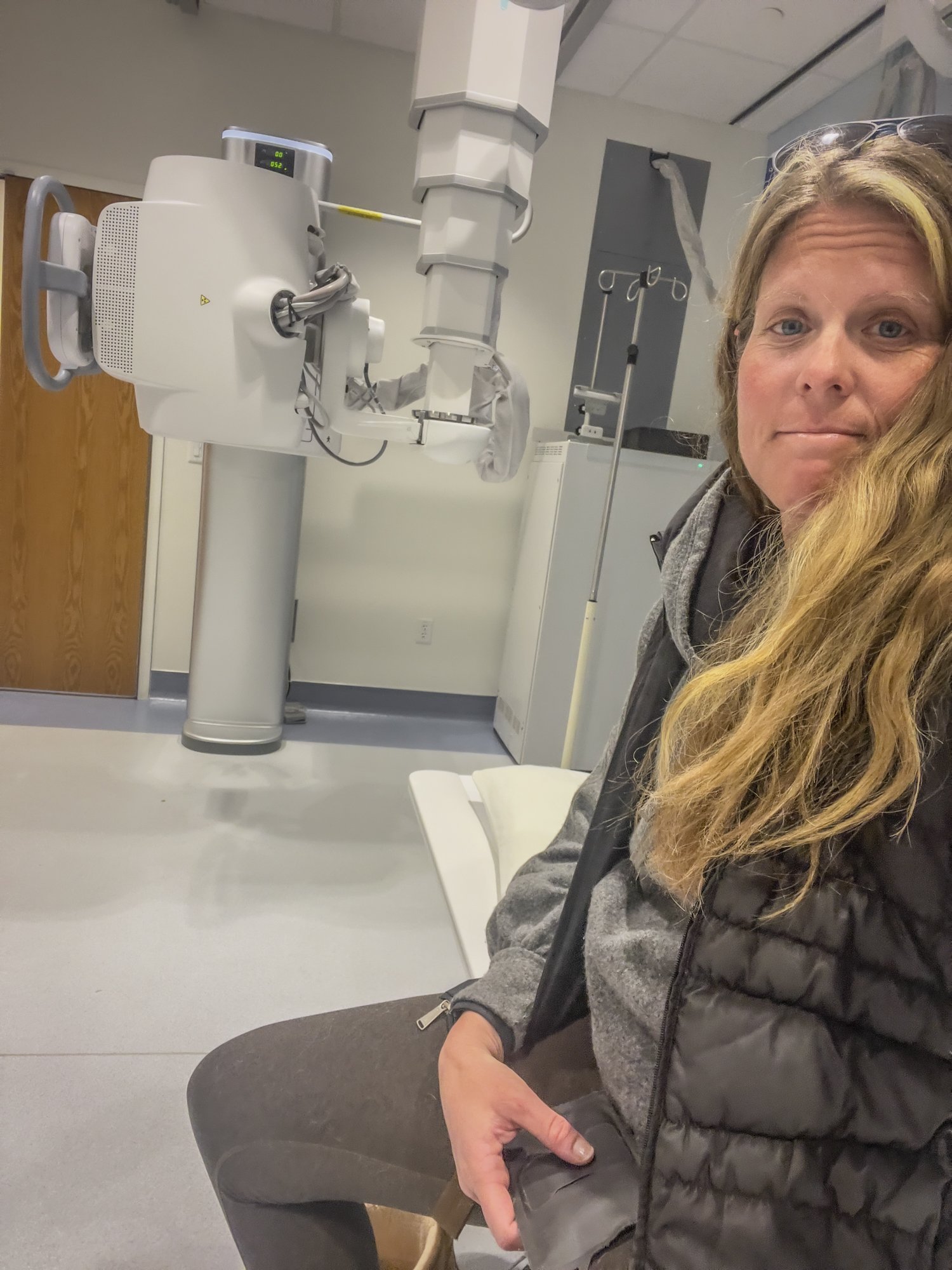

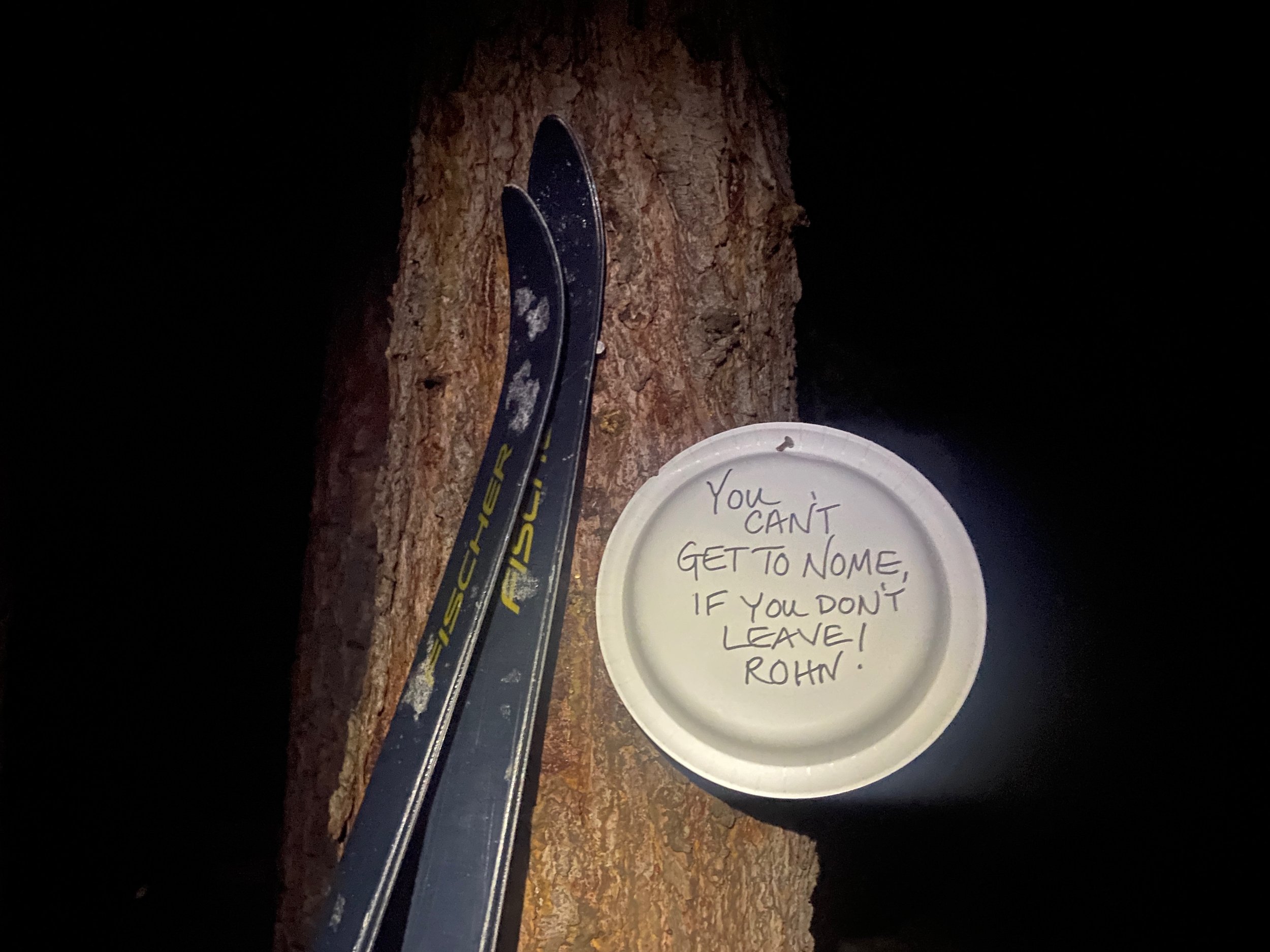

Did my feet hurt? Yes, but not any worse than in other long adventure; when I skied the Iditarod last year, my heels turned numb with nerve damage starting at Mile 150. I skied another 800 miles on those feet, all the way to Nome. It took two months for the feeling to come back.

Did my weight carrying strategy not live up to its promise? Scared of what carrying 60+ pounds for big miles each day would do to my hips (and to my energy levels), I ran a big experiment by putting wheels behind me and dragging, rather than carrying, most of what I needed for this Unsupported speed record attempt. It worked beautifully. As I already knew from skiing some 1300 miles in Alaska with a sled over the years, pulling a load behind you is much less energy consuming than carrying it on your back as long as you’re in the flats. Add hills, and any pulled item feels like an anchor five times heavier than it truly is. This is what my experience here was, too: pulling the cart worked beautifully in the flats, even on rough trail. The uphills - like climbing up the Kaibab Plateau, or going across the San Francisco Peaks - made me work for it, but my energy expenditure was still WAY lower than heaving all 67 pounds of kit up the South Kaibab trail in the Grand Canyon where wheels are prohibited. So, yes, the system worked. Better than expected even, allowing me to go hands free on the cart across burly boulders, and running so beautifully and effortlessly that I at times I found myself breaking into an easy jog on mellow trail all while “carrying” still right around 60 pounds!

So why did I drop out?

One simple answer.

My heart wasn’t in it. I didn’t feel the magic of the trail. I wanted to stop each day not because I was exhausted and couldn’t go any further, but because I was bored. (My 18 hour portage across the Grand Canyon was the notable exception to that statement - each step was a struggle on the climb out of the canyon.)

Three weeks is a long time to spend away from home and your loved ones. I was missing mine direly each day, much more so than on other adventures, and I felt lonely and sad much of the week that I spent walking the first 200 miles of the trail. These feelings inevitably intensified during darkness, of which there was a lot: with the sun setting at 5:20pm, and my days usually ending between 10pm and midnight, I had lots of nighttime hiking. I am not scared of the night, nor am I scared of being alone - I’ve had plenty of both during past adventures. This time was different. I was sad.

I often get asked how I managed to push through 30 days on the Iditarod Trail and find the mental fortitude to not give up. My answer was this: I was present, in the moment, and when I thought about what I would do with the time I could “get back” from dropping out early… I realized I didn’t want that time back. I wanted to be on the Iditarod Trail, immersed in the adventure, experiencing the growth. I only started to feel a bit over it all in Alaska on Day 26, once I was within shooting distance of the finish, and knew with some confidence that I had a reasonable chance of actually doing the thing.

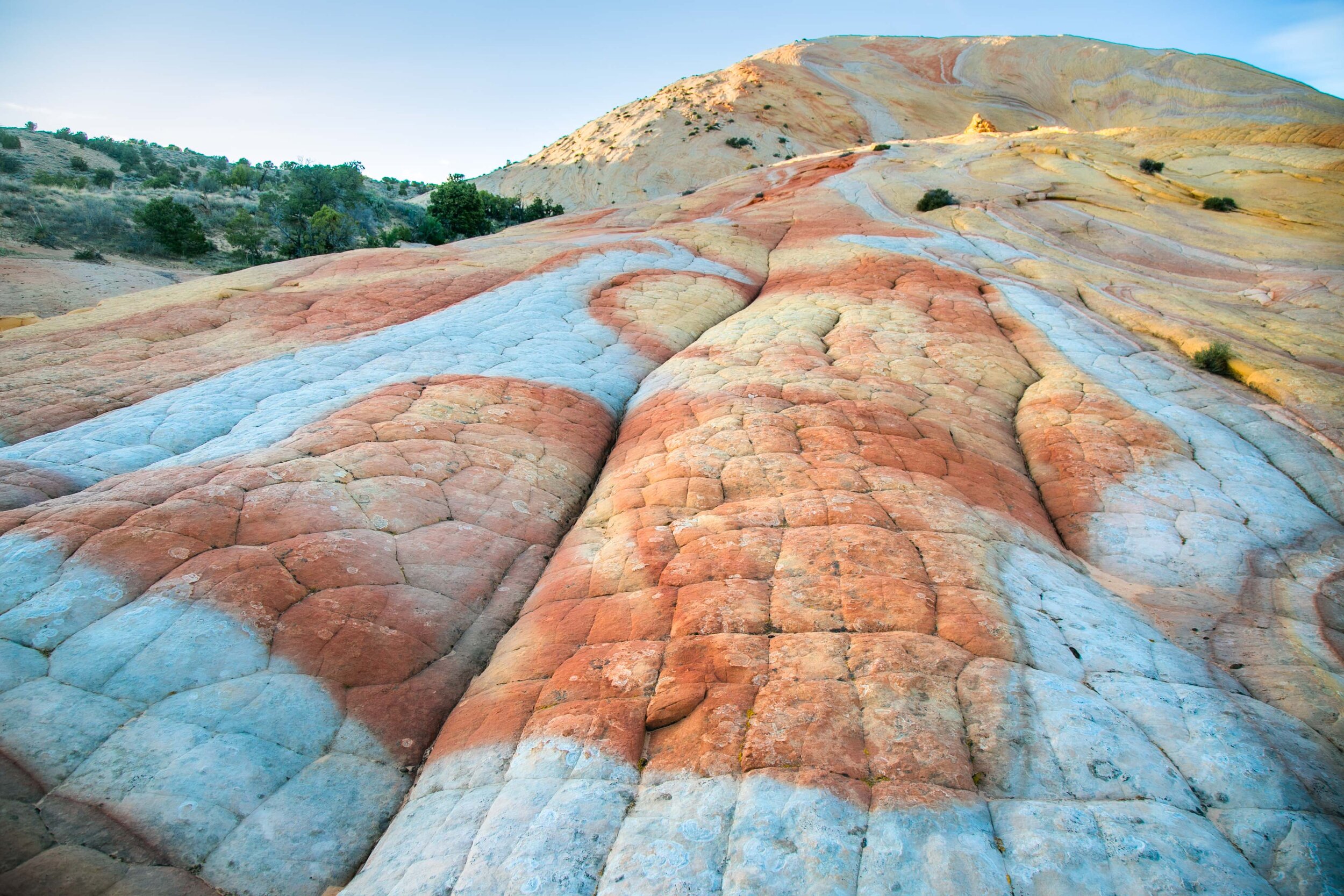

My time on the Arizona Trail was the exact opposite. Yes, I walked into it excited for the adventure and hoping that the version of myself who left the trail would be different, more capable and reflected, than the version who stood at the Northern Terminus on November 11 ready to start. Once I was walking on the trail, though, my head was swirling with so many thoughts that took me farther and farther away from wanting to be there.

The long hours of self-imposed aloneness so close to home: the AZT starts an hour from where Paul and I live in Kanab. The first 200 miles had me feeling like I was camping in the backyard of my family home on a cold dark night, longingly looking at the warm glow of the living room window lights yet barred from going in.

The memories of last year’s Supported (and aborted due to injury) attempt, where I had an amazing group of crew and pacers and friends watch out for me and accompany every step of the journey. The beauty of that experience, and its social component; such a stark contrast to this unsupported attempt.

The fact that I was excited to see the Southern portion of the trail, but that I was going to pass through 1/3rd of it in darkness without actually getting to see the landscape I was traversing.

The utter arbitrariness of the Unsupported handicap, in general and per Fastest Known Time rules. You may charge your electronics at public outlets, and throw your trash away, but apparently not sleep in a designated campground. And why did I decide to carry all my food from the start again, when there are resupply options along the way… just to prove I can?

And, the conversations around gender equity that my AZT fundraiser stirred. “What the heck is gender equity in the outdoors?” and “Women are doing rad things outdoors, we have gender equity already.” The reactions that my fundraiser announcement drove on Facebook made me realize just how far removed my immersion in this topic is from the mainstream conversation, and how much better I have to get at articulating why it all matters.

The work that I need and want to be doing right now is not to walk 35-40 miles a day so that I can pat myself on the back at the end of the trail and say “I did it”. Folks are right: there are women out there doing rad stuff; I am one of them; so is AZT unsupported record holder and ground breaking speed hiker Heather Anderson.

What I want and need to be doing right now is not to prove once more that I can do rad things; it’s to put words and logic and a call to action to the topic of what role gender plays in outdoor adventure, and how outdoor adventure is a catalyst for gender equity that reaches far, far beyond the trails, the mountains, or the seas.

So, yes: when I was skiing the Iditarod Trail I knew that I was where I wanted and needed to be, and that there was nothing else I wanted to be doing instead. Here, on this second Arizona Trail speed attempt of mine, I have come to realize the opposite: there are a hundred things (and two or three among them that are truly meaningful) that I’d rather be doing with my time. Instead of spending two more weeks on the trail in pursuit of yet another arbitrary accomplishment, I WANT that lifetime back - to spend with Paul, and to do work that matters.

Thank you for following along, and thank you for your support of the fundraising campaign for gender equity in outdoor adventure. I may not have walked the Arizona Trail to its finish, yet I don’t consider this a dropping out - I am withdrawing from this speed record attempt so I can choose to walk a different path, towards a destination that bears more significance to me, and to many others, than the Arizona Trail’s Southern Terminus.